Let's say you're heading to the movie theater to watch a quirky romantic comedy. Or you're on Disney+ watching the latest Marvel superhero show after work. Or maybe you're looking for a Netflix documentary about international cuisine.

Do any of these stories have any real basis in reality if they don't at least suggest the existence of a climate crisis?

I can already hear some of you complaining: Why does it all have to be about climate change? Let me have some fun without having to worry about the fate of the planet. Not all entertainment has to be a way to communicate environmental messages.

Agreed. But some of it should be, and now we have a tool to pressure Hollywood studios to do their part.

the news

You are reading boiling point

Sami Roth keeps you up to date on climate change, energy and the environment. Sign up to get it in your inbox twice a week.

Enter your email address

Involve me

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

You may be familiar with the Bechdel test, which measures the representation of women in films and other works of fiction. Basically, a story passes the Bechdel test if it involves two female characters talking about something other than a man.

As of today, there is a Bechdel test for global warming.

It's called the Climate Reality Check, and it was developed by the nonprofit consulting firm Good Energy and a researcher at Maine Colby College. A story passes the test only if it is clear from the events depicted on screen, on the page, or on stage that global warming is happening—and only if at least one character shows that they know it is happening.

The creators of the climate reality check program applied the tests to this year's Oscar-nominated films. Of the thirteen feature films set in Earth in the present or near future, three pass the test: “Barbie,” and most recently, “Mission: Impossible” and “Niaad.”

For me, that's not much. For Good Energy, it's a great start.

Anna Jane Joyner, the consulting firm's founder and CEO, reminded me of a report from the University of Southern California, which her company funded, that found that only 2.8% of scripted television episodes and films released from 2016 to 2020 included any reference to climate change (or Long story (list of related keywords). Three out of 13 Oscar nominees is a small sample, but it's much better by comparison.

Not only that, but Barbie and Mission Impossible were two of the most popular and critically acclaimed films of 2023.

“The Oscar nominees seem to be headed in the right direction,” Joyner said.

If you've seen Barbie and had trouble remembering the climate change reference, you're probably not alone.

From left to right: America Ferrera as Gloria, Ariana Greenblatt as Sasha, and Margot Robbie as Barbie in “Barbie.”

(Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)

As identified by Colby College students who worked with English and Environmental Studies professor Matthew Schneider-Myerson to compile climate references into this year's Oscar nominees, it's the scene in which teenager Sasha (played by Ariana Greenblatt) takes out her frustrations on Margot Robbie's Barbie. He told her: “The feminist movement has set us back 50 years, destroyed girls’ innate sense of worth, and you are killing the planet with your glorification of rampant consumerism.”

At first, I was skeptical that it was really climate related. Consumerism takes many forms.

But when I pressed Schneider-Myerson, he offered a compelling counterargument. Although the phrase “killing the planet” could theoretically refer to plastic pollution or the ozone layer, context is important. For a film coming out in 2023, his students decided it was impossible to take “killing the planet by glorifying rampant consumerism” as a climate reference, he said.

Schneider-Myerson hopes the climate reality check “will take off and go viral,” serving as a tool for audiences to put pressure on studios and for screenwriters to hold themselves accountable. He would like to see it applied to novels, plays, and video games.

“Stories are not trivial or just entertainment. Stories are the way we understand the world,” he said.

I couldn't agree more, which is why I keep coming back to this topic, the relationship between climate and entertainment.

We live in a highly polarized and fragmented world, where it is difficult to motivate people to act, and even more difficult to change their minds. If you don't think global warming is real — or if you accept that global warming is real but still don't care much about it — there's not much anyone can do about it, even if they publish really great climate journalism.

Hollywood is one of the few exceptions.

If studios can start normalizing climate and clean energy as something people talk about and care about — not just through climate-focused epic stories like the Apple TV+ series “Extrapolations,” but through quick, casual references in stories that have nothing to do with anything… last”. Environment – They can go a long way towards saving the planet.

I'm talking about quick shots of rooftop solar panels, eating fake meat hamburgers, or charging electric cars. If “Lost” were made today — I spent six years recording “Lost” rewatches for the podcast, so that’s kind of my jam — I’d advise Damon Lindelof to show a shot of Sawyer reading Bill McKibben’s 1989 climate classic, “The End of Nature “

Josh Holloway (center) as Sawyer on Lost, which aired on ABC from 2004 to 2010.

(AP/ABC photo)

These are the types of touches the Good Energy team thinks about, too.

“The psychological value of just hearing a character mention climate change in passing is very important,” Joyner said. “The purpose of this test is in no way an expression of our desire for climate to be the main focus of all stories.”

Joyner and her colleagues would like to see 50% of movies and TV shows set in the present or near future on Earth pass the climate reality test by 2027. That could mean more scenes in which newscasters describe unprecedented heatwaves, and characters have . Climate protests. Sporting events may be postponed due to wildfire smoke.

Good Energy developed the two-part test — 1) “Climate change exists” and 2) “The character knows it” — after interviewing more than 200 screenwriters, series directors, executives, and others involved in storytelling. They wanted the test to be fun, easy to use, and non-prescriptive, meaning it didn't tell writers how they should incorporate climate themes into their stories.

“A writer often shuts down if we say, ‘You have to handle it this way,’” said Carmel Banasci, editor-in-chief of Good Energy.

Until now, Hollywood studios have mostly told climate stories that promote specific solutions or warn of specific disaster scenarios, such as “How to Blow Up a Pipeline” or “Don’t Look Up.” This helps explain why Good Energy developed a climate reality check that was “the most attractive version we could think of,” Banasci says. Their goal was to invite writers to include climate “in a way that's not shoehorned in, in a way that connects to the character, and in a way that enhances the story world.”

Banaski cited Sasha's “rampant consumerism” line in Barbie, calling it “one of the most Sasha-like lines in the film.”

“I don't feel forced in any way,” she said.

I'd be surprised to see if the Hollywood power players take this seriously. And they should, even if they only care about profits.

“If climate change isn't in your story now, the audience will feel it,” Banaski said.

Don't Look Up, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence, was a very good metaphor for climate change, though I personally found it depressing and hard to stomach.

(Nike Tavernice/Netflix)

For an inside check, I ran a climate reality check via Kyle Zizzo, an unscripted television producer and former vice president and head of alternative programming at The CW. He founded the Reality of Change group that facilitates climate change and sustainability awareness in non-scripted television programming. He is also a member of the Hollywood Climate Summit Board of Advisors.

Zizo told me via email that he likes the simplicity of the climate reality check, which would make it easier for writers, executives and others to evaluate their projects and discuss changes. He appreciates that testing establishes a “baseline on which to build.”

He also wants studios to realize that passing a climate reality check “is a minimum standard.” I completely agree with this view – recognizing that global warming is real should be a “starting point,” not an “end goal,” as Zizo puts it.

“Knowing good energy, they will always be fighting for the bigger picture, so any caution on my part is focused more on how this tool is used by the wider industry, to avoid circumstances where it becomes the destination rather than the launch pad,” he said.

Zizzo also pointed out the potential dangers of Hollywood executives or other industry stakeholders claiming they have solved the problem of on-screen climate representation by taking too broad an interpretation of what counts as a global warming reference.

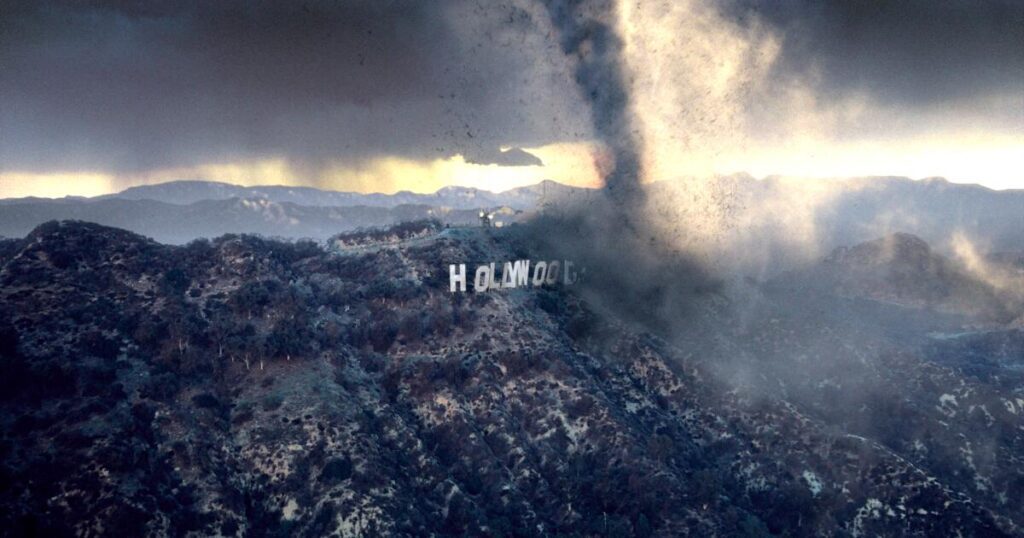

“If that history-destroying storm in the movie isn't specifically identified as the result of a climate change-induced atmospheric river, what makes it different from any other storm?” Zizo asked.

Good question. It will be up to all of us who care about the climate to take our TV shows and movies seriously, and demand that the people who make them give us what we want — stories that help make the world a better place.

We should have more data at our fingertips soon.

Schneider Myerson, a professor at Colby College, is working on another analysis that applies a climate reality check to 250 of the most popular films of the past decade. This analysis will include several other interesting metrics, including which directors have the most films that pass the climate test and whether Marvel or DC Comics has a greater number of films that pass the test.

Schneider-Myerson expects the report to be ready in April. I'll have more details then.

By the way, if you're wondering how Naiad and the more recent Mission: Impossible movie pass the climate reality test?

I haven't seen either movie, sorry to say. But according to Good Energy, a character in the movie Mission Impossible warns Ethan Hunt, played by Tom Cruise, that the next world war will be “a ballistic war on a rapidly shrinking ecosystem…breathable air.” In “Nyad,” Diana Nyad (Annette Bening) is trying to swim from Cuba to Florida when she is stung by a box jellyfish. Other figures blame the unexpected presence of jellyfish in this part of the ocean on global warming.

It's a small thing. But a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single jellyfish.

another thing

Village Theater in Westwood.

(AaronP/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images via Getty Images)

If any of you know famous film director Jason Reitman, could you send him a message to me?

Reitman directed Juno and Up in the Air, two of my favorite films. He also co-wrote “Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire,” which comes out later this month, which if we're to believe the trade headlines will take on the climate change angle.

My message is: Jason, would you be interested in hosting a climate-focused event around the time of your film's premiere, perhaps at the historic Village Theater in Westwood that you and a group of other directors just purchased? I grew up a 10 minute walk from the theater and love the place. I am delighted to moderate a discussion, which perfectly links the fictional themes of The Frozen Empire with the real climate challenges we face. I recently did something similar at the Academy of Motion Pictures Museum, and it was amazing.

So, Jason: are we there yet?

This column is the latest edition of Boiling Point, an email newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. You can sign up for Boiling Point here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on X.