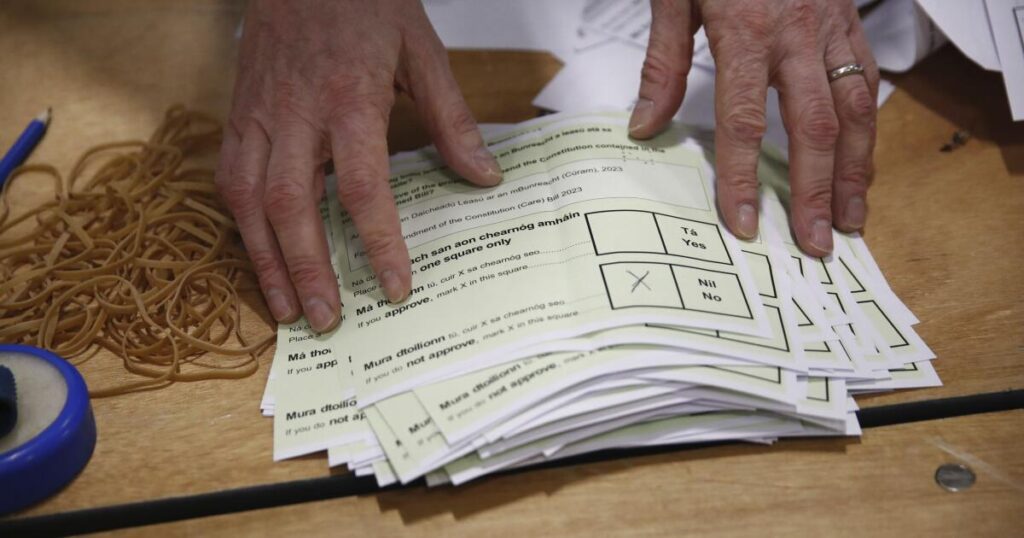

Irish voters appear to have rejected two constitutional amendments that would have removed language about women's roles in the home and expanded the definition of family.

Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar conceded defeat on Saturday during the early vote count. Varadkar, who pushed the vote to enshrine gender equality in the constitution by removing “very archaic language” and trying to acknowledge the realities of modern family life, said voters had dealt “two blows” to the government.

“Clearly we got it wrong,” he added. “While the old adage is that success has many fathers and failure is an orphan, I think when you lose by that kind of margin, there are a lot of people who have it wrong, and I'm certainly one of them.”

Opponents argued that the amendments were poorly drafted, and voters said they were confused about choices that some feared could lead to unintended consequences.

The referendum was seen as part of Ireland's evolution from an overwhelmingly Roman Catholic conservative country where divorce and abortion were illegal into an increasingly diverse and socially liberal society. The percentage of the Catholic population decreased from 94.9% in 1961 to 69% in 2022, according to the Central Statistics Office.

The social transformation was reflected in a series of changes to the Irish constitution, dating back to 1937, although the country was not officially known as the Republic of Ireland until 1949. Irish voters legalized divorce in a referendum in 1995, and supported same-sex marriage in 1995. A 2015 vote repealed the ban on abortions in 2018.

The first question dealt with a part of the constitution that pledges to protect the family as the basic unit of society. Voters were asked to remove the reference to marriage as the foundation “on which the family is founded” and replace it with a clause stating that a family may be founded “on marriage or other permanent relationships.” If it had been passed, it would have been the thirty-ninth amendment to the Constitution.

The proposed 40th Amendment would have removed the implication that women's place in the home provided a common good that could not be provided by the state. It would delete the phrase that mothers should not be required to work out of economic necessity “resulting in the neglect of their duties at home.” He would have added a clause saying the state would strive to support “the provision of care by family members to each other.”

Siobhan Mullally, professor of law and director of the Irish Center for Human Rights at the University of Galway, said Varadkar was sponsoring the scheduling of the vote on International Women's Day in the belief that people would use the occasion to repeal language about women in the world. house. The so-called care adjustment was not so simple.

While voters support removing the outdated notion of a woman's place in the home, she said, they also want new language that recognizes state support for family care provided by those who are not related. Some disability rights and social justice advocates opposed the measure because it was too restrictive in this regard.

“It was a huge missed opportunity,” Mulally said. “Certainly most people want this sexist language removed from the Constitution. There have been calls for it for years, and it took a long time to hold a referendum on it. But they proposed replacing it with this very limited and weak provision on care.”

Varadkar said his camp had not convinced people of the need to vote, let alone the issues around how the questions were worded. Supporters and opponents of the amendment said the government failed to explain why the change was necessary or launch a strong campaign.

The debate was less fraught than the debates over abortion and same-sex marriage. All of Ireland's major political parties supported the changes, including the government's centrist coalition partners Fianna Fail and Fine Gael and the largest opposition party, Sinn Féin.

One of the political parties calling for a 'no' vote was Ontu, a traditionalist group that broke away from Sinn Fein over the larger party's support for legal abortion. Ontu leader Peadar Toibin said the government's wording was so vague that it could lead to legal wrangling and that most people “don't know what a permanent relationship means.”

Opinion polls indicated support for the “yes” side in both votes, but many voters said they found the issue too confusing or too rushed to change the constitution.

“I thought it was very hasty,” said Una Uy Doyen, a nurse in Dublin. “I felt like we didn't have enough time to think about it and read it. So I felt, to be on the safe side, no, no, no change.

Caoimhe Doyle, a PhD student, said she voted yes to change the definition of family but no to the care amendment because “I don’t think it was explained well”.

“There is concern that they are taking the burden off the state to care for families,” she said.

Associated Press writers Kelly reported from Dublin and Millie from London, respectively.