Misguided investors and analysts have been forced to tear up their optimistic expectations of broad interest rate cuts this year, as rising oil and metal prices add to inflationary pressures, reigniting fears that borrowing costs will remain “higher for longer.”

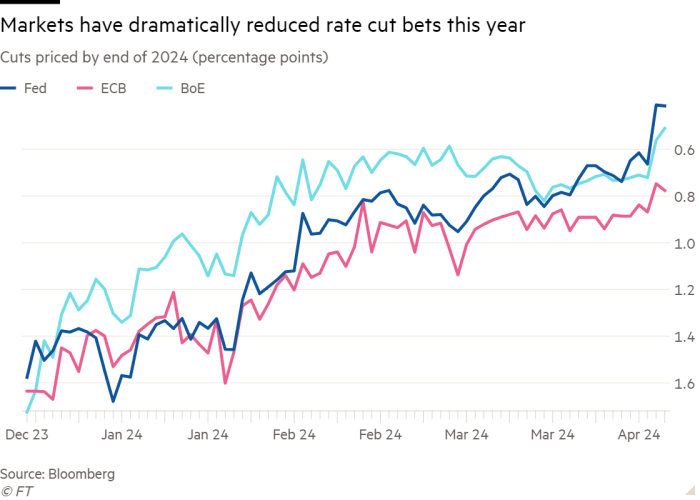

In a dramatic shift in sentiment, markets are now betting that the Fed will only cut interest rates by a quarter point or two this year.

That compares to the six or more cuts expected in January and the three cuts expected by the more conservative Federal Reserve. But after the US inflation rate this week exceeded expectations for the third month in a row, traders and fund managers are forced to seriously consider their assumptions.

The rosy outlook “has just been thrown out the window,” said Greg Peters, co-chief investment officer at PGIM Fixed Income.

“Markets have been very optimistic about the possibility of lowering interest rates,” he added, noting that investors are “behaving more rationally now than they were at the beginning of the year.”

This soul-searching stands in stark contrast to December, when the Fed gave its strongest signal yet that it would not raise borrowing costs again, and its official forecast suggested cuts of a quarter of a percentage point this year.

This has sent stock and bond prices soaring and, as investors braced for an extended period of high borrowing costs that could hurt both assets, has sparked talk that the idea of “going higher for longer” is finally dead.

But a series of huge jobs data and accelerating inflation since then dashed hopes that the Fed and other global central banks would ease monetary policy quickly.

Anthony Todd, CEO of quantitative hedge fund firm Aspect Capital, said the majority of analysts were wrong, referring to expectations of lower inflation and interest rates.

The firm, which manages about $9.4 billion in assets and whose main fund has risen 21.8 percent this year, has benefited from bets against Treasuries, which have sold off this year as investors trim their bets on interest rate cuts.

The market's pricing in interest rate cuts this year is now lower than what the Fed itself indicated in December. Some Fed officials have cast doubt on policymakers' ability to cut interest rates more than once this year, with Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic saying it is possible that rate cuts could be carried over to next year.

Further complicating the inflation outlook are rising prices for industrial metals and oil – with Brent crude oil surpassing $92 a barrel for the first time since October.

The rethink of US interest rates has also extended to European markets, with investors now pricing in three ECB and two Bank of England cuts in 2024, down from more than six cuts each at the start of the year.

“It's very clear that the narrative is changing,” said Torsten Slok, chief economist at investment firm Apollo. “The narrative uncertainty about where we're headed in interest rates is where things are so messed up right now.”

The global economy also proved more resilient than many expected, with JPMorgan's global manufacturing PMI rising into growth territory in January for the first time since 2022, and continuing to grow in February and March.

“I still think the Fed wants to cut at least once this year — but they are in no rush to do so and will wait for more data to arrive to give them a clearer view of inflation,” said Ken Shinoda, portfolio holder. Manager at DoubleLine.

Despite a rally on Friday as tensions in the Middle East pushed investors into safe-haven assets, expectations that interest rates would remain high for some time led to a global bond sell-off, pushing up government borrowing costs on both sides of the Atlantic. Benchmark US and UK government bond yields have risen 0.6 percentage points since the beginning of the year. Equivalent German Bund yields – the benchmark for the eurozone – rose by 0.3 percentage points.

However, credit spreads — or the premiums that corporate borrowers pay for issuing U.S. Treasury debt — still hover around their lowest levels in years, fueled by intense demand for new bonds and incendiary money flows.

The average spread on U.S. investment-grade bonds is now hovering around its lowest or lowest level since September 2021, six months before the Fed starts raising interest rates. The high-yield, or “junk,” spread widened after the latest CPI release, but remains near its narrowest levels since January 2022, according to Ice BofA data.

“A stronger economy with little inflation doesn't make for a bad backdrop for US companies… If you forget everything else and focus on the fundamentals, I think the fundamental piece is pretty good,” says Pigem's Peters.

So far, the rethink of interest rates has done little to calm stock markets, with the blue-chip S&P 500 index up 7.4 per cent this year – boosted by a strong US economy and excitement about the prospects of artificial intelligence.

But some investors are beginning to warn that as the reality of interest rates remaining high recedes, the stock market's vitality may run out.

“It feels like we've made easy progress, but the landscape is getting tougher,” said Mark Dowding, chief investment officer at RBC BlueBay Asset Management.

Additional reporting by Lawrence Fletcher