At the 18th minute of every Reading FC home match, fans rise up in unison to boo, regardless of the score.

The number 18 represents the total points suffered by the third-tier club due to breaches of football's financial rules in recent years, and the mockery is directed at Dai Yong, the Chinese businessman whose ownership has left one of the oldest football clubs in crisis. Opposition fans often join the protest in solidarity with Reading's unfortunate predicament.

The British government this week introduced legislation to create a new independent regulatory body for English football, which it hopes will help alleviate the kind of problems facing clubs like Reading. The new body has been promised to be given “strong powers” to force out owners deemed “unsuitable” and tasked with improving the financial sustainability of English football.

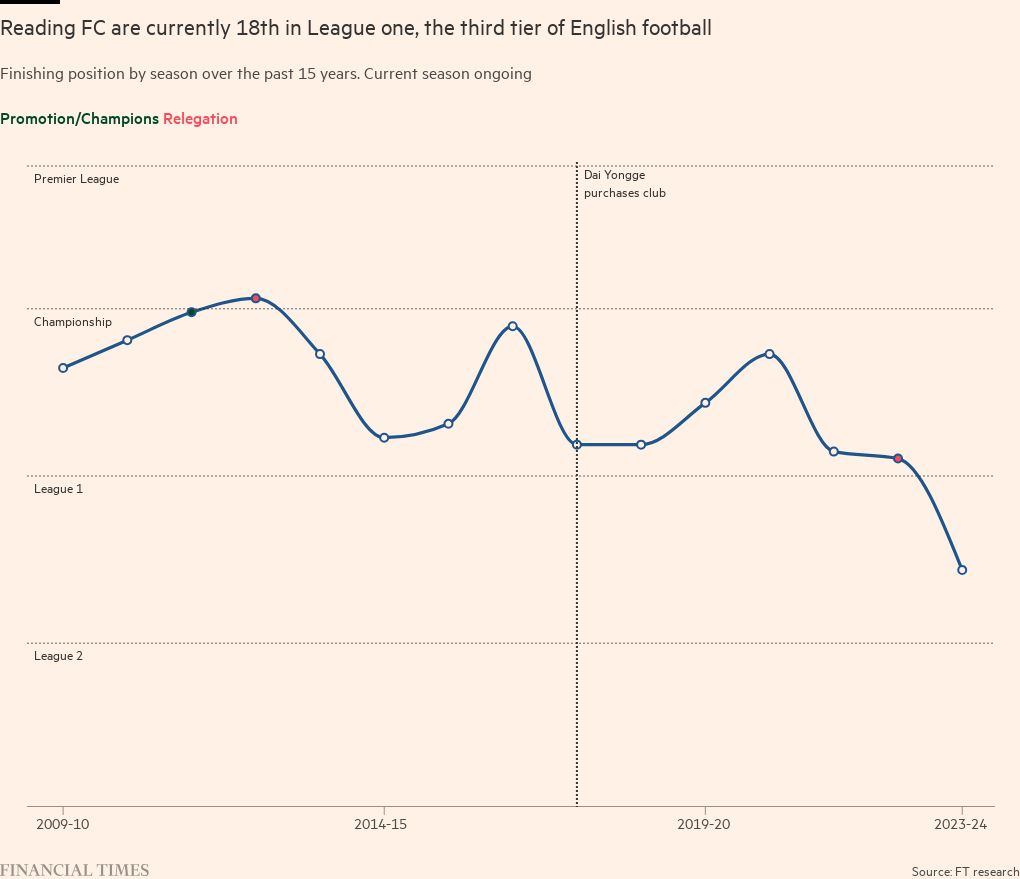

The recent troubles of Reading, founded in 1871, have been seen as a case study in why regulation is needed, after an ambitious owner overspent and under-delivered, leaving the club with unpaid bills, points deductions, relegation and the threat of collapse. .

“Football is currently structured as a casino and it attracts gamblers,” said Greg Dobell, a member of the Sell Before We Die campaign group urging the sale of the club. “We got a bad one.”

Reading was bought in May 2017 by Dai, who made his fortune in China converting air raid shelters into shopping malls, and his sister Xiu Li Huqin. The papers were signed just days before the final between Reading and Huddersfield Town. A win would have returned Reading to the Premier League, football's richest competition, but the team lost the match on penalties.

Dai's purchase came towards the end of a short-lived wave of Chinese investment in European football. Encouraged by Beijing, Chinese investors have bought or acquired stakes in several clubs, including major Italian clubs AC Milan and Inter Milan, Atletico Madrid in Spain, and a number of English teams such as Manchester City, Aston Villa and Wolverhampton Wanderers. Many of these investments have since been dismantled.

After Reading lost in the 2017 play-off final, Day poured money into the chase for promotion to the Premier League. A state-of-the-art training ground was built while new players were signed on huge salaries, but performances on the pitch failed to match the outlay.

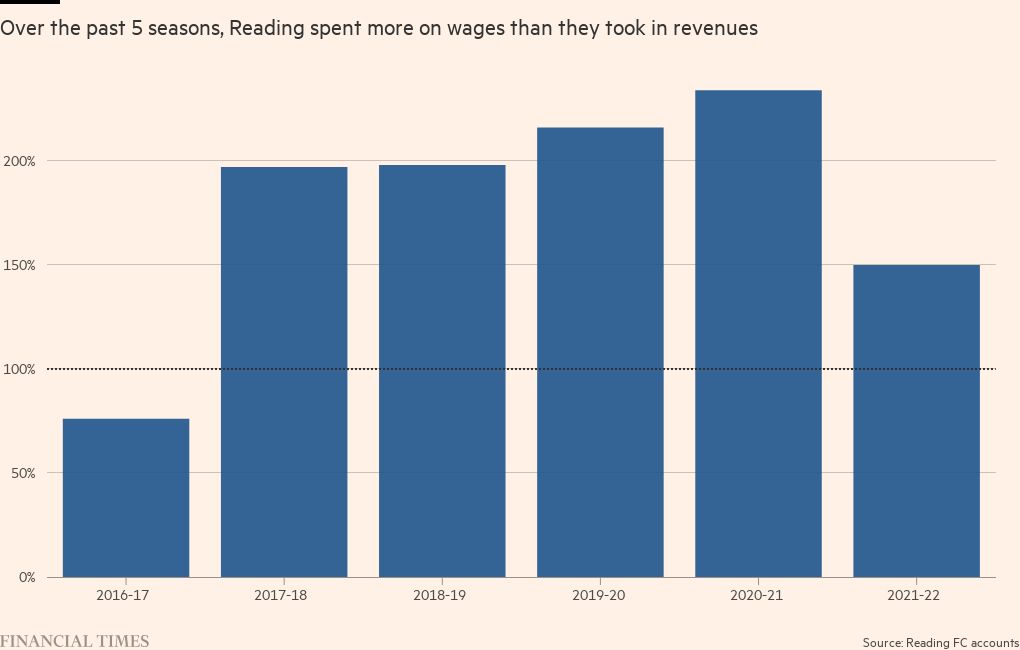

The lavish spending caught the attention of football's governing bodies. In November 2021, the EFL dropped six points from Reading for breaching financial rules. At the time, the club's annual wage bill of £32m was more than double its total revenue. Reading have been banned from buying new players almost ever since.

Reading recorded an annual pre-tax loss of £17m in its latest set of accounts covering the year to June 2022. It lost £36m the year before. Deloitte estimates the club's net debt of £220m is the largest in English football outside the Premier League.

However, Reading's poor financial situation is consistent with the wider landscape of English football, with most clubs relying on wealthy owners to cover persistent deficits.

Kieran Maguire, a football finance expert at the University of Liverpool, estimates that, based on earnings before interest and tax, teams in England's second tier typically lose around £500,000 a week, while the average wage bill in the league is over Average. revenue in all but one of the past 10 seasons.

“Clubs are losing money before they turn on the floodlights. It's not a sustainable business from a conventional point of view,” he said.

At Reading, further penalties for late payments followed, contributing to the club's slide into the third tier of English football at the end of last season after two decades in the top two divisions.

In February, the club was deducted a further two points after failing to pay money owed to HMRC, while Day was fined £100,000 by the EFL and ordered to deposit enough money to cover the club's monthly wage bill.

The Premier League instructed Day to “provide his club with the appropriate resources necessary” and accelerate “its efforts to sell a majority of its shares to new owners.”

However, the league has no power to force a sale, and can only impose more fines and deduct more points, or take the nuclear option of expelling Reading from the league.

James Sunderland, the Conservative MP for nearby Bracknell, said: “As a fan, what is happening here is devastating.” “It is clear that we need to protect football better from rogue owners – and if you want the perfect test case, this is it here.”

Day's problems are not limited to reading. Two other football clubs he owned – Beijing Renhe and KSV Rosselare in Belgium – were liquidated.

Meanwhile, his main company, China Daily, ran into problems. The Hong Kong-listed company's shares have been suspended since October 2022 after facing lawsuits from lenders regarding late payments on bank loans. The company said in December that bank deposits worth 612 million renminbi (£67 million) had been frozen.

After cost cutting, Reading no longer has a media relations team. The club declined to comment. Efforts to contact Dai for comment through the club and at its registered address in Hong Kong were unsuccessful.

Despite a rich fan base, proximity to London and a highly rated youth academy, Reading's prospects are uncertain. Fans have been told that the club is running a £1m deficit for the month and there is no clarity on whether or not Day will provide the necessary funds.

Some fans have suggested emergency fundraising, while others hope failure to pay bills will eventually push the club into administration and speed up the sale process.

The biggest fear among Reading supporters is the possibility of assets being sold, leaving the club with little except a name and badge to offer any new owner. Liquidation remains a real threat.

“The fact that some fans are now praying for management tells you everything,” said Carolyn Parker, another Sell Before We Dai member.

The 24,000-seat Select Car Leasing Stadium used by the team is separately owned by Dai. The club recently agreed to offload its Bearwood training ground to local rival Wycombe Wanderers but the deal collapsed this week after Reading fans discovered a clause in local planning documents preventing any other team from using it.

For now, all hopes are pinned on Day reaching a deal to sell the club. Talks have been held with potential buyers in recent days, according to people familiar with the matter, but the club has said nothing publicly.

While the new regulatory body will be tasked with tackling some of the issues affecting clubs such as Reading, legal experts are skeptical that it will bring about real change.

Simon Liff, head of sports law at law firm Mishcon de Reya, said the regulatory body's new powers over ownership were “grabbing the headlines”, but “in reality it would be very difficult to effectively nationalize a football club” if the owner was deemed to be problem.

As for whether this might change the behavior of club owners, the dream of reaching the Premier League is likely to continue. “The one thing I've learned about football is that football doesn't teach you anything,” Maguire said.

Additional reporting by William Langley in Hong Kong and Wang Xueqiao in Shanghai.