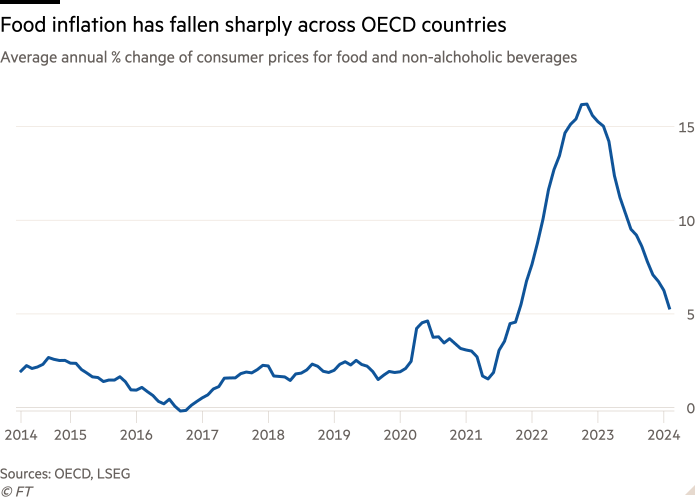

Food inflation in rich countries has fallen to its lowest level since before Russia's large-scale invasion of Ukraine, with a slowdown in price growth easing pressure on millions of families hit by two years of rising food costs.

The annual change in consumer food prices across 38 industrialized countries fell to 5.3 percent in February, down from 6.2 percent the previous month and well below the peak of 16.2 percent in November 2022, according to the latest OECD data.

Food prices rose in 2022 due to higher energy costs and lower trade due to the war in Ukraine, while larger-than-expected droughts and coronavirus-related supply chain disruptions also took their toll. High prices have contributed to 333 million people suffering from acute food insecurity in 2023, according to the World Food Programme.

“We have seen the worst of food inflation,” said Carlos Mera, head of agricultural commodities at Rabobank.

“Agricultural commodity prices have fallen significantly in the past two years, since prices peaked in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine, and this is acting as a deflationary force even in… [the] retail level.”

“Supply chains have fully returned to normal, gas prices have fallen to levels considered historically more normal, and Ukrainian grain exports have resumed via the Black Sea corridor,” said Thomas Vieladek, an economist at investment firm T. Rowe Price.

“Taking these factors apart suggests that the slowdown in global food inflation is likely to continue.”

The OECD is expected to comment on the food price figure, the lowest since October 2021, in its broader inflation update on Monday.

Separate figures published by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) on Friday showed that food prices including cereals, sugar and meat generally fell from their record peak in 2022.

The FAO food commodity price index rose slightly to 118.3 in March, after a seven-month decline. But the number is still 9.9 points lower than last March.

The decline in food inflation was widespread across industrialized countries in February, with the latest OECD reading halving or nearly halving from the recent peak.

In the United States, annual food price inflation fell to 2.2% in February, down from its peak of 11.4% in August 2022, and the lowest since May 2021.

In the UK, food and non-alcoholic drink prices rose 5 per cent in the year to February, the lowest level since the start of 2022 and well below the 45-year high of 19.2 per cent in March 2023.

Across the eurozone, the annual rate of food and non-alcoholic beverage prices fell to 2.7 percent in March, the first reading below 3 percent since November 2021, according to preliminary Eurostat estimates.

Some countries are still suffering from higher than normal food prices. The surprise rise in the FAO index during March was driven by higher prices for vegetable oils such as soybean, sunflower and rapeseed, due to a seasonal decline in production and an unexpected rise in demand from Southeast Asia.

“Overall, food inflation is falling in the developed world and emerging markets, but we are seeing pockets where things remain difficult, most notably countries suffering from exchange rate pressures and dependent on imports,” said Kiran Ahmed, chief economist at Oxford University. Economics.

Turkey, an OECD country, recorded annual food price inflation of 70.4 percent in March as the lira continued to weaken against the dollar. Likewise, food inflation accelerated to an annual rate of 37.9 percent in February in Nigeria, which relies on food imports and has recently devalued its currency.

There has also been a continuing increase in food prices in many countries where rice is a staple food, after the Indian ban on rice exports affected supplies. Benchmark rice prices rose 25 percent annually in February, according to the International Monetary Fund, and food inflation continued to rise in countries that depend on Indian rice imports, such as the Philippines and Bangladesh, by 3.4 percent and 9.44 percent. In the same month.

However, the decline in wholesale prices of agricultural products, especially grains, indicates continued decline in inflation in most countries in the coming months.

“In past price rises, after a delay, [agricultural] “Producers have shifted to meet demand,” said Steve Wiggins, senior research fellow at ODI, a global affairs think tank. “I expect to see prices continue to fall.”

The decline in agricultural commodity prices did not prevent consumer food prices from rising in general because commodities represent a relatively small proportion of retail costs.

The price of bread, for example, also depends on the cost of labor, marketing, packaging, energy, distribution, profit margins and promotion. Mira at Rabobank estimates that the price of wheat represents at most 10 percent of the total cost of bread.

Commodity prices are also passed on to consumers with a time lag, meaning that recent declines in agricultural prices will be reflected on grocery shelves next year.