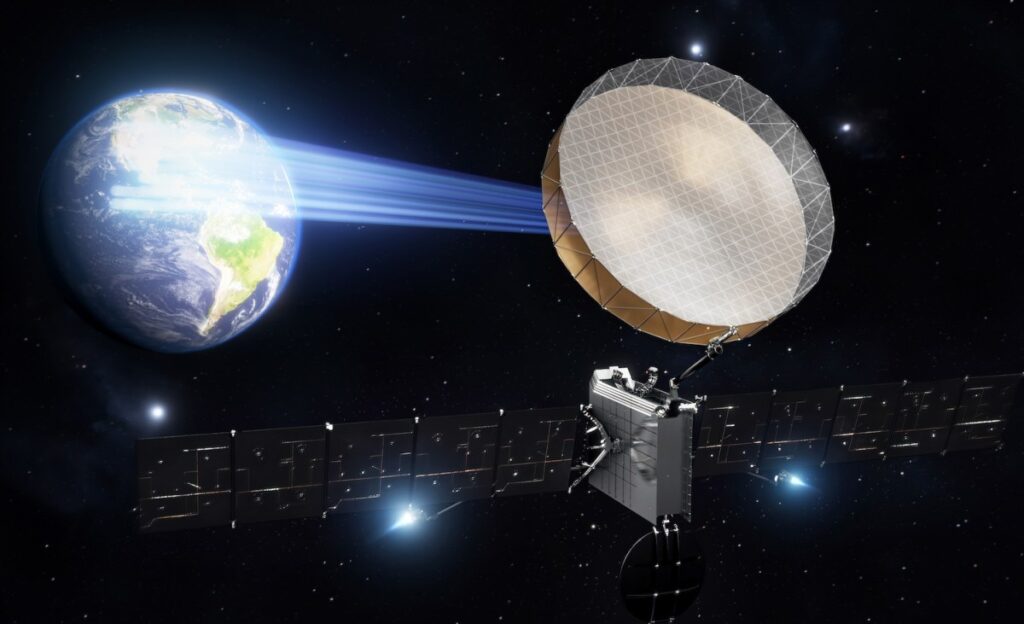

Astranis has unveiled a new generation of communications satellites that will serve broadband to customers on Earth from geostationary orbit, but are faster and smaller than any satellite out there. They believe that the future of orbital communications lies not only in higher orbits, but also in the possibility of customers – government and commercial – having their own satellite network.

The new class of satellites, dubbed Omega, will provide about 50 gigabits per second of bandwidth in both civilian and military Ka bands – making it clear from the start that this technology is intended to be a dual-use technology.

Astranis builds and operates small, relatively broadband satellites in high orbits, and sells that capacity to telecommunications and Internet service providers. The company has contracts to provide capacity to service providers in Mexico, the Philippines, Alaska and Southeast Asia.

The startup wins the prize thanks to the relatively small size of its geostationary satellites, which are typically bulky and, as a result, easy to track and potentially attack.

“We need to move to a more flexible architecture. No more big, fat, juicy targets!” Astranis CEO John Gidmark said at an event at Space Symposium where the news was announced.

The improved bandwidth is thanks to the Astranis Next Generation Software Defined Radio, but the signal is propagated more efficiently; Whereas the previous generation sent out an array of coherent beams, like floodlights, the new generation looks more like a large LED array, providing an even signal across a much larger area. Although the number of points that can be delivered depends on the customer and use case, in theory it runs into the millions, Jedmark said. The satellites use existing Ka-band receivers instead of a dedicated antenna like a Starlink antenna.

Speaking of competitors: When asked how the orbital communications market will develop in the near term, Jedmark was very optimistic. The appetite for bandwidth is virtually unlimited, he said, at least at the prices they can offer, which are much lower than legacy GEO data connections.

Image credits: Astrans (Opens in a new window)

Notably, Astranis said the satellite will support specific waveforms of interest to the Department of Defense, such as the protected tactical waveform, so it can still provide capability even in contested environments. Astranis' proposal—many small satellites in Earth orbit—is a far cry from older technology, which generally relied on very large, very expensive, and unmaneuverable satellites in Earth orbit. In other words, they exploit opponents.

Like the company's existing satellites, Omega will have the ability to maneuver in geostationary orbit using all-electric propulsion on board. Astranis said the more efficient propulsion would allow it to maintain its station for at least a decade, as well as perform plenty of repositioning and other maneuvers. By then, the next generation will likely be ready to take over.

However, Astranis' breakout product will be customer-specific satellites. Obviously countries have dedicated spy satellites and the like, but these cost hundreds of millions of dollars and are often funded from defense budgets. But even multinational companies don't tend to have that kind of money, for this purpose at least — and if they do, they don't tend to have satellite management departments. Astranis plans to offer essentially “satellite as a service” instead, where the entire satellite (or part) can be commissioned for use by a single customer for an upfront, monthly fee.

Jedmark declined to name any of the companies that have expressed interest or have been courted in other ways, and noted that energy and oil and gas companies are the obvious ones, with holdings across broad geographies and demand for a significant amount of secure satellites. Data. He also said that although there are no official plans yet to approach the lunar market, there is a great opportunity for future growth.

The company aims to complete its first Omega satellite in 2025 and launch it into orbit in 2026. The plan is to launch based on six satellites at that time, with up to 24 satellites launched annually after that depending on how manufacturing scales up.