It was the era of the Wild West, when white men from the East were flocking to Arizona to reap the golden bounty of the land, seizing land and making laws.

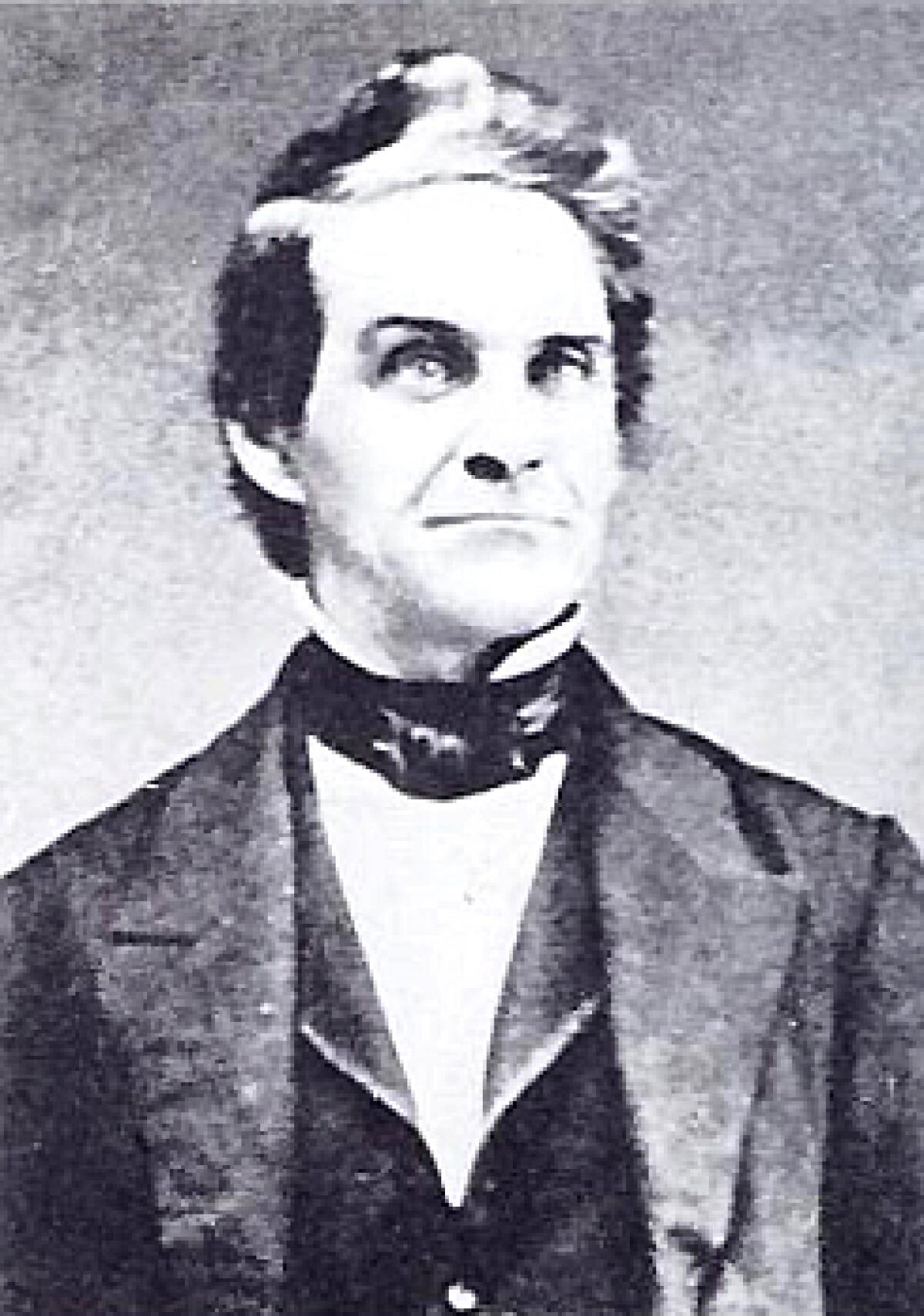

William Howell, a New Yorker charged with writing the law that would establish Arizona as a territory, opened the law books in a neighboring state as a model: California. He copied large portions of the state's legal text — including a clause that criminalizes abortions except when the mother's life is in danger.

On Tuesday, 160 years later, the significance of Howell's words rose again, when the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that the state would return to its original abortion law, barring doctors from offering it in all cases except when the mother's life is in danger.

“History doesn't happen in a vacuum,” said Melanie Sturgeon, retired state archivist and co-founder and president of the Arizona Women's History Coalition. “You have to understand what is happening…in the region or state and who is next to us, and what is happening at the national level that affects us.”

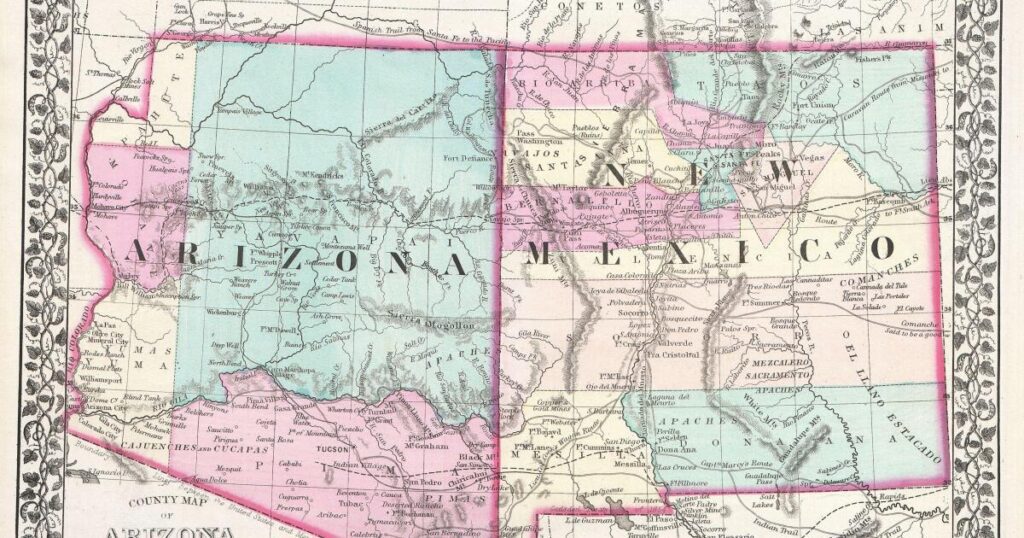

California, with its promise of gold, began attracting a wave of visitors from the East in the late 1840s, and soon coalesced to form a state in 1850, the first in the West. California's southeastern neighbors soon followed suit. In late 1863, Arizona seceded from New Mexico to become its own emerging territory.

Over the next year, Anglo-American men traveled from the east to lay down the foundation structure for Arizona. Among those key early figures was Howell. Born and raised on a New York farm, Howell began teaching at 16, became a newspaper editor at 19, and by 24 was practicing law, John Goff wrote in his article “William T. Howell and the Howell Blog in Arizona.”

Justice William Howell, a New Yorker, wrote the law that would enshrine Arizona as a territory, based on the law books of a neighboring state: California.

(Arizona Historical Foundation)

Howell was married three times, remarrying after the deaths of his first and second wives, and had children with both women, according to Goff. He spent most of his adult life in Michigan, where he rose through the ranks of the state legislature and twice served as speaker pro tem before traveling to Arizona.

“Howell is a somewhat obscure figure, little remembered in Arizona, and largely forgotten in his home state of Michigan,” Goff wrote.

In 1862, then-President Lincoln wrote: “When the Arizona Territory is organized, let William T. Howell, of Michigan, is a judge there.”

Howell moved to Arizona the following year and soon established a court in Tucson. In the midst of civil war ravaging the country, Howell delivered a speech to an assembled grand jury that “addressed at length the need to protect the rights of the people by affording equal justice to all,” Goff wrote.

As one of his first assignments as an associate judge in Arizona, Howell “reviewed the law books of California, New York, and other states in search of laws suitable for the territory,” according to a 1970 book titled “Arizona Territory, 1863-1912; Arizona Territory, 1863-1912; The State of Arizona, 1863-1912; The State of Arizona, 1863-1912.” Political History” by Jay Wagner.

“Arizona basically… copied California’s law,” Sturgeon said.

In California's statutes, Howell found and listed – almost word for word – its provisions regarding abortion. The paragraph is included in a section of Arizona law about the penalty for poisoning another person:

“And every person who gives or causes to be given or taken any medicinal substances, or uses or causes to be used any instruments whatsoever, with the intention of aborting any woman who is in the stage of pregnancy shall, if duly convicted, be punished,” states each. of California and Arizona law, adding that an exception would be made from the law for a physician “who, in the performance of his or her professional duties, deems it necessary to abort any woman in order to save her life.”

Howell received a total of $7,500 for his work on the job, and Arizona's founding document was named the “Howell Code,” according to Wagner's book.

“Part of the reason I think this becomes part of the law in the West is to make sure white women don't have abortions,” Sturgeon said. “I don't think they cared much if Mexicans and Native Americans had abortions, but they were very concerned.”

Sturgeon said the birth rate had been declining since the beginning of the 19th century, as industrialization moved people from farms to cities, reducing the need for as many children as possible to support their families.

While modern abortion laws vary from state to state — and some include exceptions for rape or incest — Arizona's original law was strict. That was fairly typical at the time, because the age of consent in Arizona, as Sturgeon pointed out, was 10 years.

“It was assumed that if you got pregnant when you were 10, you had seduced that uncle, that neighbor, that older brother or something,” she said. “So there is nothing in our laws about rape or incest.”

Sturgeon said she read court transcripts to judges and juries questioning children about their role in attracting an older man.

She said: “There is a poor child who carries a child until the end of his birth… and suffers from all this trauma resulting from being harassed and impregnated by a relative or family friend, and they have to live with that for the rest of their lives.” “Because they were just supposed to be the ones seducing someone.”

Shortly after Arizona's law was put in place, ads for self-induced abortions began appearing in newspapers, Sturgeon said. The ads used the same term used in Arizona law — “medical substances” — to refer to abortions.

“Any time you saw an ad that said 'the Portuguese drug,' that was a euphemism for 'this will lead to miscarriage,'” she said.

Howell's stay in Arizona was short-lived. As Goff wrote, Howell received word that his third wife had also fallen ill in Michigan, “and may not live until the judge comes home.” Howell took a leave of absence from his job in Arizona to return to his dying wife's side.

He probably never returned to the West.