The double murder case against football star and actor OJ Simpson, who died of cancer on Thursday at the age of 76, changed the television landscape forever.

Network news was still a limited enterprise in 1994, when more than 30 million viewers tuned into the evening news each night. The broadcasters of the time — Tom Brokaw on NBC, Peter Jennings on ABC, Dan Rather on CBS — were powerful arbiters of what the audience needed to know.

The Internet was nascent, and CNN, available in about half the country via cable, was considered a tier below the Big Three.

But the scene changed on June 17, 1994, the day of a slow-speed police pursuit on Los Angeles freeways of Simpson in his white Bronco, two days after the brutal murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend. Ron Goldman.

A reported 95 million people watched Simpson evade capture. The chase was broadcast across all three networks, local stations and CNN, and became an iconic “where have you been” television moment on par with the Kennedy assassination in 1963 or the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger in 1986.

NBC's feed of the chase was presented simultaneously alongside coverage of the NBA Finals game between the Houston Rockets and New York Knicks, making it one of the most bizarre split screens in the history of the medium.

From that moment on, the country was transfixed by every aspect of the case, from Simpson's indictment to his stunning acquittal that left him a free man again on October 3, 1995. An estimated 150 million viewers watched it live.

Network news traditionalists were reluctant to give much coverage to the Simpson story at first. But viewers' interest in the case made it impossible to ignore.

“It showed the importance of following the audience rather than having the anchor tell you what's important,” said Tami Haddad, a veteran news producer who now heads the Washington Artificial Intelligence Network, a forum for Beltway types to discuss artificial intelligence. “This is a big sea change.”

Bill Whitaker, who covered the story for the CBS Evening News, recalled the inconsistency at serious news organizations.

Media outside the Los Angeles Criminal Courts Building attempt to question defense attorneys for murder defendant OJ Simpson, Johnnie Cochran Jr., right, and F. Lee Bailey, left, as they enter the building.

(Mike Nelson/AFP via Getty Images)

“There was a love-hate relationship with the story because it took on the feel of a soap opera,” Whitaker, now a correspondent for CBS News' 60 Minutes, said in an interview. “But it was inevitable. As a news organization you had to cover it.”

“There was racing. It had sex. It had drugs. It had an athlete turned movie star. Every element would get people's attention.”

Jennings, a Canadian international affairs specialist, was particularly dismissive of the popular nature of the story.

But Brokaw, who was an anchor at KNBC in Los Angeles when Simpson emerged as a star running back at USC in the late 1960s, recognized its importance and led the cause every night. As a result, his show “NBC Nightly News” rose to No. 1 in the ratings, topping “ABC World News Tonight,” which had held the top spot for years.

“It came at the perfect time to combine celebrity news, traditional news and court news,” said Steve Friedman, who was executive producer of NBC's “Today” show at the time. “Traditional news people didn't understand the gravity of the story. You couldn't take your eyes off him. People of my generation said, 'You have to cover him.'”

The downside, Whitaker saw, was that the lines between serious newscasts, tabloid-style outlets and entertainment-driven programming were becoming blurred. “It changed the media landscape,” he said. “In the TV viewer’s mind, we are all in one basket.”

Old guard news departments had no choice but to cover the story while cable networks showed it to viewers around the clock.

A few years ago, CNN and Court TV actually saw a spike in viewership during their live coverage of the Menendez brothers' first trial for the murder of their parents. Before that, the William Kennedy Smith rape trial captivated audiences. Cameras in the courtroom gave the media inexpensive hours of live coverage that they could package into an ongoing saga that kept viewers hooked.

These cases demonstrated the desire for true crime stories. But The Simpson Trial became the first major success in the genre.

For about a year, Whitaker was stationed outside the courthouse in downtown Los Angeles, reporting each night atop a rickety six-story scaffold to get a view among the throngs of media crews surrounding the area each day.

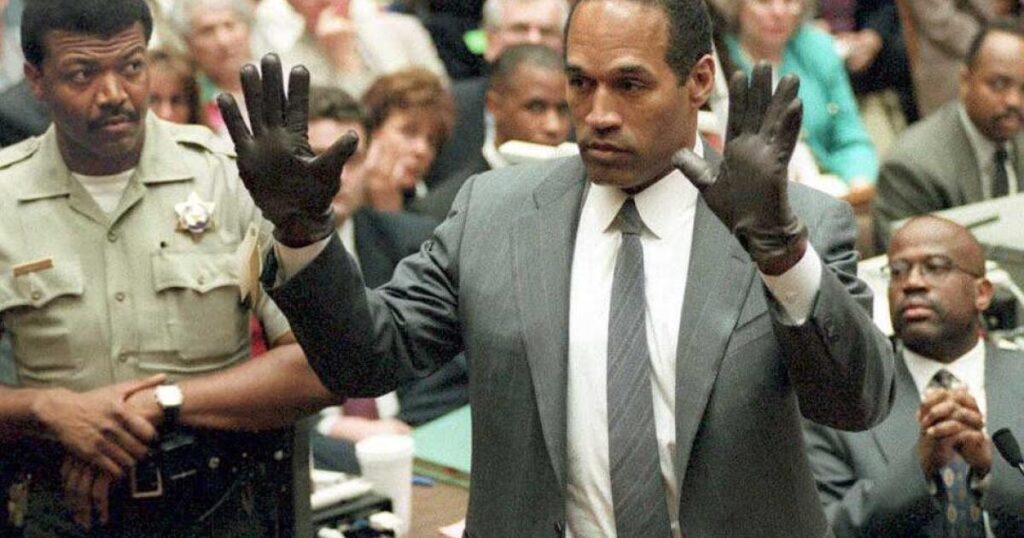

More than once, Whitaker would prepare a story in the morning, then delete it in the afternoon because there was another shocking new development. “I've never been in a trial where there was a gasping moment almost every day,” he recalls. “Police Department. Mark Fuhrman's racial slurs. The glove doesn't fit.”

Even the technicalities of the case kept viewers glued.

“Every day was a big news day,” said Dan Abrams, a veteran legal analyst who hosts a nightly show on the cable network NewsNation. “The DNA expert is testifying today about the scientific evidence and the public remains engaged. We have never seen anything like a nine-month event when there is an announcement that the public follows every day.”

Round-the-clock coverage of the trial spawned television stars among the participants. Defense attorney Johnnie Cochran was asked to sign outside the courtroom, Whittaker recalls. Vendors were selling hats with the names of the attorneys in the case on them, Abrams recalled.

“No rock star or president had the kind of esteem that Johnnie Cochran did at the time,” Abrams said.

Cochran, prosecuting attorneys Marcia Clark, and Christopher Darden got television jobs after the trial. Even Foreman became a news contributor, and still appears on television to comment on issues.

Journalists and commentators who covered the case saw their careers skyrocket. Court TV became a feeder to larger outlets. Greta Van Susteren went from being an attorney and legal commentator to an anchor on several cable networks.

Abrams left his job at a law firm to become an associate producer at Court TV and was promoted to reporter before the Simpson case heated up. It ended up making him a fixture on television news. He still feels conflicted about the tragic circumstances that set him up for success.

“It was the first big story I ever covered,” Abrams said. “I always had a little bit of guilt about the idea that the brutal murder of two people helped my career.”

“And again, when you cover legal stories, you cover a lot of homicides,” he added. “My focus was a lot on the legal points. But I did my best to get to know the victims' families well. To look at the matter without their point of view would be too harsh.”