Thanks to a cash windfall five years ago, Gov. Newsom said he has done away with a state budget “gimmick” that one of his predecessors relied on to reduce the deficit by about $800 million during the Great Recession.

The accounting trick, adopted in 2009, delayed state employee salaries from the end of one fiscal year on June 30 to the beginning of the next fiscal year on July 1. A decade later, Newsom spent nearly $1 billion to end the hoax, with one caveat.

“If I use it in six years, in a recession, forgive me,” Newsom said.

At his request, Newsom and lawmakers agreed to use the budget gimmick next year even though California is not in a recession.

The tactic is one of several maneuvers Democrats are relying on to reduce a historic budget deficit of at least $37.9 billion by pushing their spending problem into another year.

Of the $17.3 billion in budget cuts agreed upon by Newsom and Democrats so far, only $3.6 billion are actual cuts.

Lawmakers made the first of those cuts on Thursday, passing a budget trailer that cuts unspent funding allocations in 2022-23 and 2023-24 by $1.6 billion. Although Newsom described the changes as part of an “early action” deal to reduce the deficit in April, many of the cuts will not be reflected in legislation until June or later.

So far at least, Newsom and lawmakers have largely relied on mechanisms other than cuts to reduce the deficit: borrowing $5.2 billion, delaying and deferring $5.2 billion in funding for state-sponsored programs to later years and tapping $3.4 billion in separate state funds. Democrats also agreed to withdraw at least another $12.2 billion from the rainy day fund to cover their spending.

Budget watchers and Republican lawmakers have criticized the strategy, saying resorting to smart accounting now and declining California's savings account while the economy remains strong will make the state more vulnerable to drastic cuts if there is a recession in coming years and revenues decline.

Newsom's critics blame the governor and Democrats for overspending and running deficits. The “trick” is an example of what critics see as Democrats' failure to make the kind of tough choices that California families are forced to make when they spend more money than they bring in.

“They're doing things you normally do in times of recession, and there's no recession here,” said David Crane, president of the California Governors League, a nonprofit that seeks to oppose the influence of labor unions over state government. “You should not rely on reserves to cover a budget deficit if your revenues are 50% higher than they were when you took office.”

General Fund revenues, which the state uses to pay for most public services, were $140 billion when Newsom took office in 2018-19. The governor's January budget assumes revenues of more than $214 billion, a 53% increase, for the upcoming fiscal year when Democrats plan to cut the rainy day fund in half.

According to UC Anderson forecasts in March, California's economy is growing faster than the rest of the country and the possibility of a U.S. recession is fading. Newsom regularly touts the strength of the state's economy.

“Although challenges remain ahead — particularly state and local government financing, homelessness and out-migration — the forces driving California’s economy remain strong,” the UCLA economists wrote.

H.D. Palmer, spokesman for the governor's Treasury Department, said the cuts approved by Democrats so far are part, but not all, of the solutions to budget problems with more decisions to be made in June. He also noted that more than 70% of the general budget is spent on K-12 education, health care and human services.

“If you don't agree with those solutions, that's OK. What specific proposals would you make to make up for that in terms of programmatic cuts?” he asked budget critics.

Assembly Republican Leader James Gallagher of Yuba City said he would start by funding the basics, such as education, infrastructure and public safety, and then identify other resources the state has for it.

Newsom often touts all-one-time funding in his past budgets, which he said would be easy to stop if the state went from surplus to deficit. But he continued to support many of his costly policy priorities, such as expanding Medi-Cal to all eligible low-income immigrants, regardless of their legal status. A state audit also found that California failed to monitor the effectiveness of its costly homelessness programs, on which Newsom and lawmakers have spent $20 billion over the past five years.

“The $73 billion deficit is no joke,” Gallagher said. “It's a serious problem that we have to address. That makes me think the governor just wants to see this problem through the rest of his term and leave this problem to someone else.”

A combination of late tax deadlines and overspending based on inaccurate budget projections has led to budget deficits, which occur when spending exceeds projected revenues.

Newsom and lawmakers expected revenues to fall below expectations due to a falling stock market, rising interest rates and rising inflation, but the deficit would be much worse than what the state recorded last June. The Newsom administration last set the deficit at $37.9 billion in January, though a more recent estimate from the Legislative Analyst's Office suggests it could reach $73 billion by the time the governor unveils his revised budget proposal in mid-May.

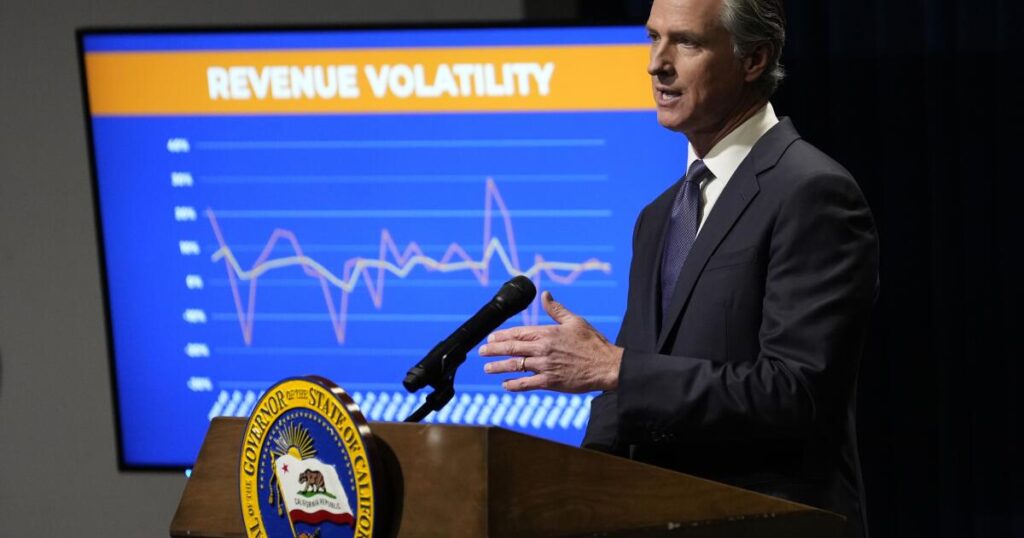

California's state budget depends largely on income taxes paid by the highest earners. Revenues are subject to fluctuations, depend on capital gains on investments, bonuses to executives and windfalls from new equity offerings, and are difficult for the state to predict.

The governor repeatedly blames the deficit problem on the federal government's decision to delay the 2022 income tax filing deadline from April to November last year due to winter storms.

In a typical budget year, state government has tax receipts in hand before the governor unveils his revised budget proposal in mid-May and before he reaches a final spending agreement with lawmakers in June. The tax delay forced lawmakers and the governor to enact the current budget in July based on estimates of how much money the state would collect in tax revenue by the November deadline. These estimates were greatly wrong.

The legislation approved Thursday goes back and reduces unspent funding in previous and current budget years. The changes include cutting $45 million to protect communities from wildfires, $88 million for watershed resiliency, and cutting funding to expand broadband internet access by $34 million, among other cuts.

The bill was part of lawmakers' “early action” and the governor announced they would make a decision in April to reduce the deficit by $17.3 billion before a May review. But only $3.3 billion of the cuts he claimed they would implement can be passed into law now, and the majority will be included in the final budget agreement, along with other cuts, approved this summer.

“We put forward this early action plan to safeguard our progress and protect essential programs so we can responsibly spend time and energy on the most challenging decisions to responsibly close the remaining budget gap,” said Senate President Pro Tem Mike McGuire (D-Healdsburg). During debates in the Senate on Thursday. “And we will do just that.”

Democrats are trying to make up for the budget crisis before May, when the updated estimate shows a deeper deficit. Democrats also took the unusual step of requiring the state Department of Finance to subtract $17.3 billion from the estimated deficit before the budget review in May, making the deficit appear smaller before many changes are reflected in the law.

“This budget is nothing but smoke and mirrors and behind-the-scenes deals made by the party in control,” said Sen. Brian Daley (R-Pa.).

Delaying salaries from June 30, 2025, to July 1, 2025, is among the changes that Democrats agreed to, but they will not vote on until this summer.

While Crane, a political donor to Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas and dozens of other lawmakers, opposes Newsom's decision to use the budget trick again, he said the “biggest sin” is the decision to draw from state reserves in the absence of a recession. Newsom would have to declare a budget emergency in order to do so under state law.

“My only hope is that by the time the May amendment comes around, he will be able to say I won’t have to dip into reserves anymore,” Crane said.