Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up for the Work & Careers myFT Digest – delivered straight to your inbox.

Sue Gray was back in the news last weekend.

In fact, the former civil servant has rarely been out of the news since she unexpectedly resigned to become chief of staff to Labor leader Sir Keir Starmer last year.

This time, the Mail on Sunday devoted almost an entire page to the woman it described as “a real-life party version of CJ Craig,” the fictional White House chief of staff in the TV series The West Wing.

This was a small beer for someone accused of everything from plotting the overthrow of Boris Johnson to spying for the British government in Northern Ireland, which she denies, of course.

But to me, one of the most wonderful things about Gray is not what she did, but what she failed to do: go to college.

I still remember my shock when I heard a former senior Whitehall staff mention it on the BBC in 2022, when Gray was second permanent secretary in the powerful Cabinet Office. This made her one of the most senior officials in the office, ranking just below the permanent secretaries who ran Whitehall departments.

For context, the number of permanent secretaries who had never been to university at this time was almost zero, according to a 2019 report by the social mobility charity Sutton Trust. Most of them went to one of only two universities, Oxford or Cambridge, as did most senior judges, ministers and diplomats.

To illustrate again, the proportion of the general population going to Oxbridge was less than 1 per cent, and only 7 per cent went to the private schools that educate most permanent secretaries, chief justices and lords.

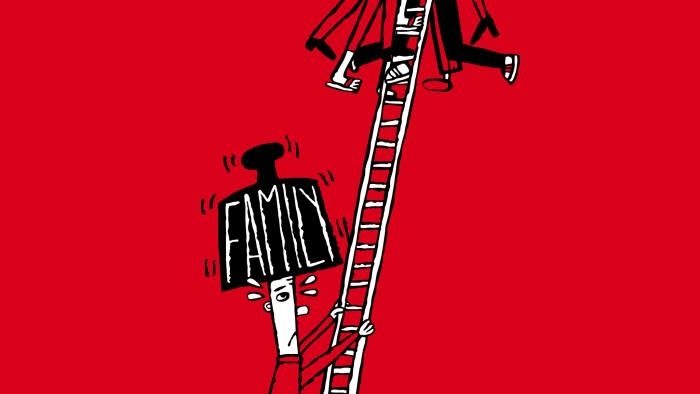

Education is not the only measure of class. Parents' occupations are also important. But Gray remains an outsider in a country where a small elite still has a large say in how things are run. The Labor Party she is trying to elect has plans to smash the “class ceiling” which by some measures is a bigger problem in the UK than in some similar countries.

But such plans are not new. Calls for a “classless society” were made thirty years ago by then Conservative Party leader John Major, the last UK Prime Minister who did not go to university.

What's new is that some employers are finally starting to address the problem. In the process, they reveal some important things about working life in modern Britain, such as the fact that class can have a greater impact on your chance of promotion than gender, race or sexual orientation.

UK professional services firm KPMG revealed this in a pioneering analysis of the career paths of 16,500 of its partners and staff that it published just over a year ago.

The company measured class by checking what an employee's highest-earning parent does for a living, a method used by PricewaterhouseCoopers, the law firm Slaughter & May, and other groups that address social class diversity.

KPMG data showed that people from working-class families take 19 per cent longer on average to change grade, or up to one year, than those from higher socio-economic backgrounds. Progress was slower for working-class employees who were a) female or b) had an ethnic minority background.

Interestingly, the class gap was reflected at the highest levels of KPMG, where working-class employees progressed fastest. It's not clear why, says Jenny Baskerville, head of inclusion, diversity and equality at KPMG in the UK. But she told me that these people may be “so exceptional” that once they finally reach leadership positions, they “lean into their identity” and work their way up to the partner level faster.

Despite all this, there is still a huge pay gap among working-class people in the UK. One study puts it at £6,291 – or 12 per cent – for working-class professionals. It is almost three times larger in the financial sector, which is thought to have the highest pay gap of all occupations.

Regulators have so far avoided making social class reporting mandatory, fearing the burden of reporting in a sector where few companies collect the necessary data. Experts say this needs to change, with students from disadvantaged backgrounds with a first-class degree from a prestigious university still less likely to get an elite job than more advantaged students with poor second-class degrees. I agree.

Groups like KPMG show that once class backgrounds are known, employers can know who is affected and what can be done to make sure all talented people advance. This is just not fair. It's also just good business.

pilita.clark@ft.com