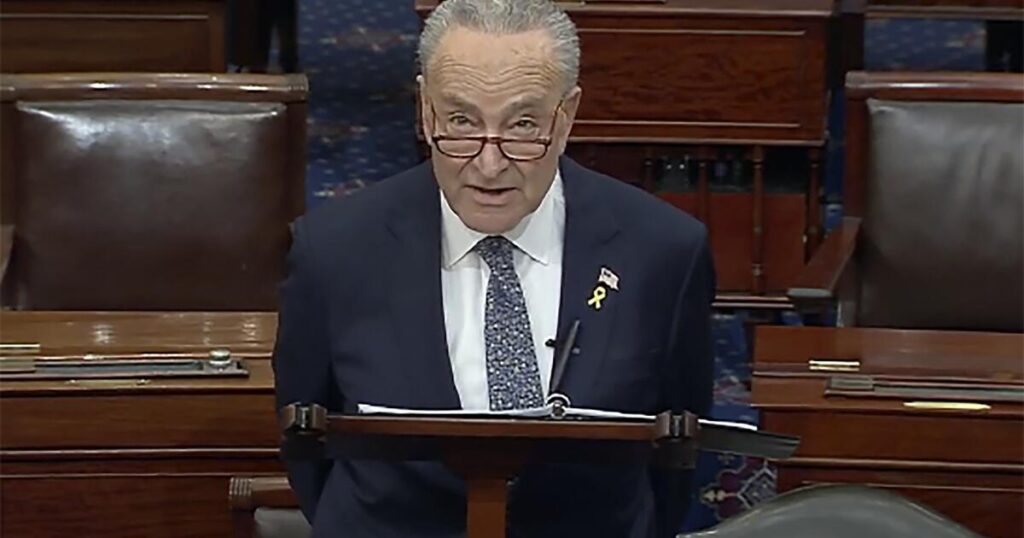

Republicans and Israeli officials were quick to express their anger after Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer strongly criticized Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's handling of the war in Gaza and called on Israel to hold new elections. They accused the Democratic leader of violating the unwritten rule against interfering in his close ally's electoral politics.

Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell responded to Schumer by saying, “It is hypocritical for Americans who go too far to interfere in our democracy to call for the removal of a democratically elected leader.”

House Speaker Mike Johnson said Schumer's call for new elections was “inappropriate.” Even Benny Gantz, Netanyahu's political rival and member of Israel's wartime cabinet, said Schumer's comments were “counterproductive.”

Schumer's stinging rebuke of Netanyahu — the senator said the Israeli leader had “lost his way” and was an obstacle to peace — was certainly provocative, but not a breach of norms. US leaders, as well as US allies, often interfere in electoral politics beyond water.

Look no further than the historically close and complex relationship that American presidents and congressional leaders have negotiated with Israel's leaders over the past 75 years.

“It's an urban myth that we don't interfere in Israeli politics and they don't try to interfere in our politics,” said Aaron David Miller, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace who has worked as a Middle East negotiator. In Republican and Democratic administrations. “We intercede and they intercede for us.”

In 2019, just weeks before Netanyahu faced a tough election, then-President Trump suddenly announced that the United States recognized Israel's sovereignty over the disputed Golan Heights, giving Netanyahu a political boost when he needed it most.

In 2015, Republican House Speaker John Boehner invited Netanyahu to address Congress during sensitive negotiations over the Iranian nuclear program and shortly before national elections in Israel.

Boehner did not coordinate the invitation with the Obama administration. Obama declined Netanyahu's invitation to visit the White House during the visit, with White House officials saying such a visit so close to the Israeli elections would be inappropriate.

The standard that Obama set for visiting the White House was not the standard that Bill Clinton adopted years ago. In April 1996, Clinton invited Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres to the White House to sign a $100 million anti-terrorism agreement shortly before the Israeli elections. Years later, Clinton admitted in an interview that he was trying to give Perez a boost with voters.

It didn't work; Peres lost to Netanyahu.

In practice, staying away from allied elections was more a stated American value than a sacred protocol. Edward Frantz, a University of Indianapolis historian, says U.S. leaders often displayed a “varsity-for-junior varsity” approach to how openly they were involved in friends’ domestic politics. The larger the allied country's economy, the less likely American leaders are to interfere openly in its elections.

“American politicians want it to be both ways,” Frantz said. “There are moments when American leaders want and need to speak out and make their opinions known. But there is a reason to stay close to the broad outlines of the election. We do not want foreign governments to interfere in our internal policies either.”

The lines have become blurrier in recent years, and are being tested by how world leaders handle the rematch between Biden and Trump in November.

This month, during a visit to the White House on the 25th anniversary of Poland's accession to NATO, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk made no secret of his desire to see Biden win another term.

“I want you to know that your campaign four years ago was truly inspiring for me and for many Poles,” Tusk and Polish conservative President Andrzej Duda alongside him said. “We are encouraged by your victory. Thank you for your determination. It was really important, and not just for the United States.”

Tusk later suggested that Johnson, the Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives, was responsible for Washington's impasse over a spending bill worth $60 billion in aid for Ukraine, which is suffering from a shortage of ammunition and weapons in its war with Russia.

“These are not political skirmishes that are important only here, on the American political stage,” Tusk said. He told reporters that Johnson's failure to act could “cost thousands of human lives in Ukraine.”

Biden this month criticized Trump for hosting Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who described Trump's potential return as “the only serious chance” to end the war in Ukraine.

Hungary, like the United States, is a member of NATO. Orban has become an icon for some conservative populists for his advocacy of “illiberal democracy,” replete with restrictions on immigration and gay rights.

During a recent campaign event, Biden noted that Trump was meeting with Orban, and said that the Hungarian leader was “looking for dictatorship.” Hungary summoned the US ambassador to Budapest, David Pressman, to express its dissatisfaction with the president's statements.

White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said that the president stands by his statements.

“Our position is that Hungary has engaged in an attack on democratic institutions, and this remains a matter of grave concern to us,” Sullivan said.

Schumer's comments in the midst of Israel's difficult five-month war constitute a new tension in the relationship between the United States and Israel.

This relationship has already seen tensions rise between Biden and Netanyahu as the Palestinian death toll rises and innocent civilians suffer as the United States and others struggle to get aid through the Israeli blockade to Gaza. National elections are scheduled for 2026 in Israel, although they could be held earlier.

Biden, in a brief exchange with reporters on Friday, said he thought Schumer gave a “good speech.” But the president and White House officials stopped short of supporting Schumer's call for elections.

There were other moments of deep tension in US-Israeli relations.

President Eisenhower pressured Israel by threatening sanctions to withdraw from the Sinai in 1957 in the midst of the Suez Crisis. Reagan postponed delivery of F16 fighter jets to Israel at a time of escalating violence in the Middle East. President George H. W. Bush froze loan guarantees worth $10 billion to force Israel to stop settlement activity in the occupied territories.

But Schumer's push for new elections risks entering uncharted territory.

“All those other crises were one-time incidents,” Miller said. “It was an effort to move Israel in a focused and detached way on a specific issue. “What we have now, years into Netanyahu’s premiership, is a fundamental crisis of trust, which goes to the core of the relationship between the United States and Israel.”

Madhani writes for The Associated Press.