When hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin said at an industry conference this week that the U.S. bond market was due for some discipline, he was voicing the concerns of many investors about the impact of massive government spending and debt issuance plans.

US government spending is “out of control,” he told a Futures Industry Association meeting in Florida. “Unfortunately, when the sovereign market starts to put the hammer down in terms of discipline, it can be quite brutal.”

But while there may have been good reasons for so-called bond vigilantes — hedge funds and other traders who punish free-spending nations by betting on their debt or simply refusing to buy it — to turn their attention to the Treasury market, analysts say they did. So far it has not been achieved.

After a brief wave of awakening occurred in the fall of last year, bond investors doubled down on the main driver of fixed-income markets: the path of interest rates. While the supply of new Treasuries has been large, so has demand, as investors in the United States and abroad try to secure relatively high yields ahead of the expected cycle of interest rate cuts.

“The whole fear of supply gatekeepers and bonds is a load of rubbish,” said Bob Michel, chief investment officer and head of the global fixed income, currencies and commodities group at JPMorgan Asset Management. “I don't see any evidence of that at all.”

“For at least the last six months, clients have been coming to us and asking: ‘Where can I get into the bond market? When will I enter the bond market? “Everyone has money to put in bonds,” Michelle added.

The yield on 10-year Treasury bonds fell from a peak of 5 percent in October to 4.3 percent, reflecting rising bond prices. Inflows into US bond funds in the first week of March reached the highest level since 2021, according to EPFR data.

The heyday of the shadowy market vigilantes who struggled to rein in government deficits was in the 1990s during the presidency of Bill Clinton, when concerns about the federal budget deficit pushed the yield on 10-year bonds from 5.2 percent in October 1993 to 8.1 percent in November. November 1994. The government responded with efforts to reduce the deficit.

But betting against bond markets became an increasingly dangerous game in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, as central banks, including the Federal Reserve, bought up massive amounts of their government debt in an attempt to lower borrowing costs and stimulate their economies.

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, the Fed's large purchases have thwarted the efforts of gatekeepers, despite record borrowing needs in the United States.

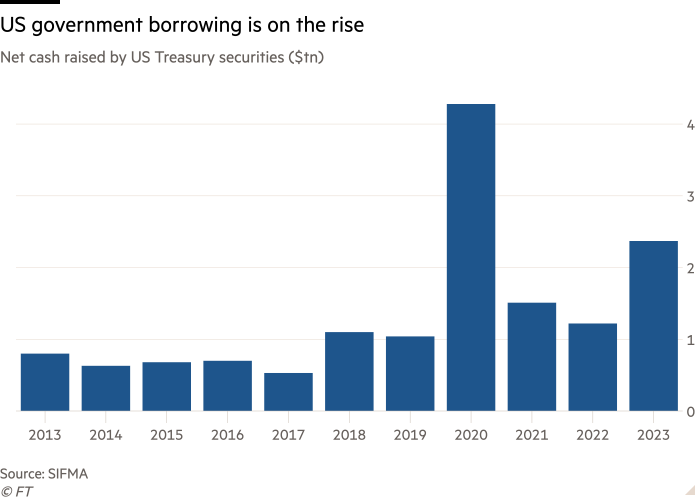

But as the Fed shifts from buyer to seller, the amount of US Treasury sales has remained high, suggesting that conditions may finally be turning in the custodians' favor. The amount of Treasury bonds outstanding is expected to rise by $1.7 trillion this year, according to Goldman Sachs. While this is less than last year's increase, it would be more likely for longer-dated bonds, which are riskier for investors and harder for markets to digest.

Last fall, Treasury yields reached their highest level in 16 years. While that was driven by the Fed's message of “higher rates for longer,” some investors said it was exacerbated by the sheer weight of issuance, after the US Treasury said in August it would increase the size of its debt auctions.

The episode was an echo of the UK's bond market revolt a year earlier, when investors balked at then-prime minister Liz Truss' unfunded tax cuts, sending government bonds into a tailspin.

Edward Yardeni, the researcher who coined the term in 1983, declared that the bond vigilantes were back. Markets are working to rein in rampant borrowing, Kevin Zhao, head of global sovereign debt and currency at UBS Asset Management, said in an October interview on CNBC. .

But yields then fell sharply, as markets shifted from concerns about a prolonged period of high borrowing costs to feverish speculation about when and how quickly the Fed would cut them — reaffirming the primacy of monetary policy as a driver of bond market action.

“There was a short-lived protest by bond guards,” Yardeni said in an interview this week. “But they're back in napping mode. A napping doesn't mean they're gone for good. The supply problem is still there, but the bond market doesn't seem to care much about it.”

Some analysts say the abundance of cash accumulated in money market funds, which invest in very short-term government debt, serves as a potential source of continued demand for Treasuries. US money market assets reached a record $6.1 trillion this week, according to ICI data. Some of this “dry powder” will likely find its way into longer-term debt once investors become sufficiently convinced that the Fed is willing to cut interest rates, Michel said.

But for some investors, the threat of vigilantism remains. Treasuries are at risk of a major sell-off if Donald Trump's victory in the US presidential election in November is accompanied by concerns about a level of government spending similar to that seen in the United States, said Vincent Mortier, chief investment officer at Amundi, Europe's largest fund manager. Triggered by the 2022 government bond crisis.

Additionally, if stubbornly high inflation means the Fed is unable to cut interest rates as quickly as the market expects, investors could turn their attention back to the massive wave of supply of Treasuries coming, according to Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management. .

The Treasury held record-sized auctions of two- and five-year bonds this month, which will grow again in April and May. Potential bond guards “are still in a sleepy state,” Slok said. “But a really weak auction might wake up [them] higher.”

Additional reporting by Jennifer Hughes in Boca Raton, Florida