Good morning. It's Monday, February 26th. I'm Jenny Gould, a reporter on the Times's early childhood education staff — and a mom who's done her share of trips to the pediatrician's office. Here's what you need to know to start your day.

the news

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California to get news, features and recommendations from the LA Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

Enter your email address

Involve me

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

California kids don't get to see a doctor. this is the reason

Pediatricians recommend that children go to the doctor for regular checkups frequently. For parents, this means taking your child at least six times in the first 15 months, twice more by age two and once every year after that.

But in California, something is wrong. Although 97% of children have insurance coverage, many never actually go to the doctor. California ranks 46th out of 50 states and the District of Columbia in the percentage of children ages 0 to 5 who had a child welfare visit in the past year.

The problem is exacerbated for more than half of California's children covered by Medi-Cal, the state's health insurance for low-income residents — including 1.4 million children between the ages of 0 and 5.

The California State Auditor has issued two scathing reports over the past five years detailing the problem and placing the blame on the Department of Health Care Services. The administration said it has made significant improvements to help parents get quality child care. But after digging into the data and speaking with families and advocates across the state, I found that serious problems persist.

What is the problem?

Only 42% of children with Medi-Cal got recommended visits and screenings in 2021, and data for the most recent year was available, according to the state auditor. This means that 2.9 million children in California miss out on care each year. For younger children, the situation is even worse: 60% of one-year-olds and 73% of two-year-olds did not receive recommended services.

Children who skip recommended preventative care can suffer real health consequences: increased frequent visits to the hospital, delayed diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders like autism, missed cases of lead poisoning, and even an increased risk of contracting a vaccine-preventable disease like measles or whooping cough.

Families cite countless reasons why they cannot take their children to see a doctor. Some had to wait months for an appointment. Others couldn't get their Medi-Cal coverage to work or were caught in a nightmare loop of bureaucracy. In rural areas, some parents say there is no doctor near them who accepts Medi-Cal. Many low-income families say they simply cannot take time off work or access transportation.

The state bears the blame

In 2019, the state auditor found that the Department of Health failed to ensure that the majority of children in Medi-Cal received the preventative care to which they were entitled. They blamed low payment rates for pediatricians and weak oversight of health plans, and presented the administration with a list of reforms. In a follow-up report for 2022, auditors said management was still not doing enough. Access to children has become worse.

Nearly all children in Medi-Cal get their care through one of 25 managed care plans that administer the program on behalf of the state. Each plan gets a certain amount of money per member each month to provide care. They can keep what they don't spend, and make money by trying to eliminate costly and unnecessary care.

But the monthly rate paid for children is much lower than for the elderly or individuals with chronic diseases, and there is not much fat to be cut in their care. As a result, the plans generally did not focus on their youngest members. “Children are a rounding error,” said Dr. Alice Kuo, a pediatrician and professor of health policy at the University of California.

Ultimately, the Department of Health Care Services is responsible for making sure plans provide children with the care they are entitled to under federal law, auditors determined.

The Ministry of Health did not agree to an interview, but in an email response to my written questions, it said that although the focus on the COVID-19 pandemic slowed its response, children’s health was a top priority, and it has since implemented nearly all recommendations and began reforming the Medi-Cal program. The agency said one of its most important measures is imposing fines on plans that fail to provide care for children.

“To their credit, there is a tremendous amount of transformation going on,” said Alexandra Parma, director of policy research and development at the First Five Center for Children's Policy. “But implementation is really difficult.” Because the changes are relatively new and not yet reflected in available data, it is difficult to know the extent of improvement in access to care.

Earlier this month, the fines became public: Only one of the state's 25 Medi-Cal plans met all minimum standards related to children's health. So far, 18 companies have fallen short of expectations and been fined between $25,000 and $890,000, including poor performance in children's health.

Read more: Limited wait hours and appointments: Why California kids aren't going to the doctor.

Today's most important news

A homeless encampment under Highway 101 on Cahuenga Street in Hollywood has become entrenched, neighbors say.

(Wally Scalig/Los Angeles Times)

Politics and elections

Science and environment

Crime and the courts

More big stories

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Great reads today

Asylum-seeking migrants line up on February 2 at a cold temporary camp site for processing after crossing the border near Jacumba Hot Springs, California.

(Gregory Paul/Associated Press)

Migrant apprehensions along the border are up in California and down in Texas. Experts told The Times' Andrea Castillo that a combination of factors was likely behind the shift, including Texas' anti-immigration policies.

Other great reads

How can we make this leaflet more useful? Send comments to basiccalifornia@latimes.com.

For your downtime

(Gwen Huerta/For The Times)

Out

stay in

Finally…a great picture

Show us your favorite place in California! Send us photos you've taken of iconic California locations – natural or man-made – and tell us why they're important to you.

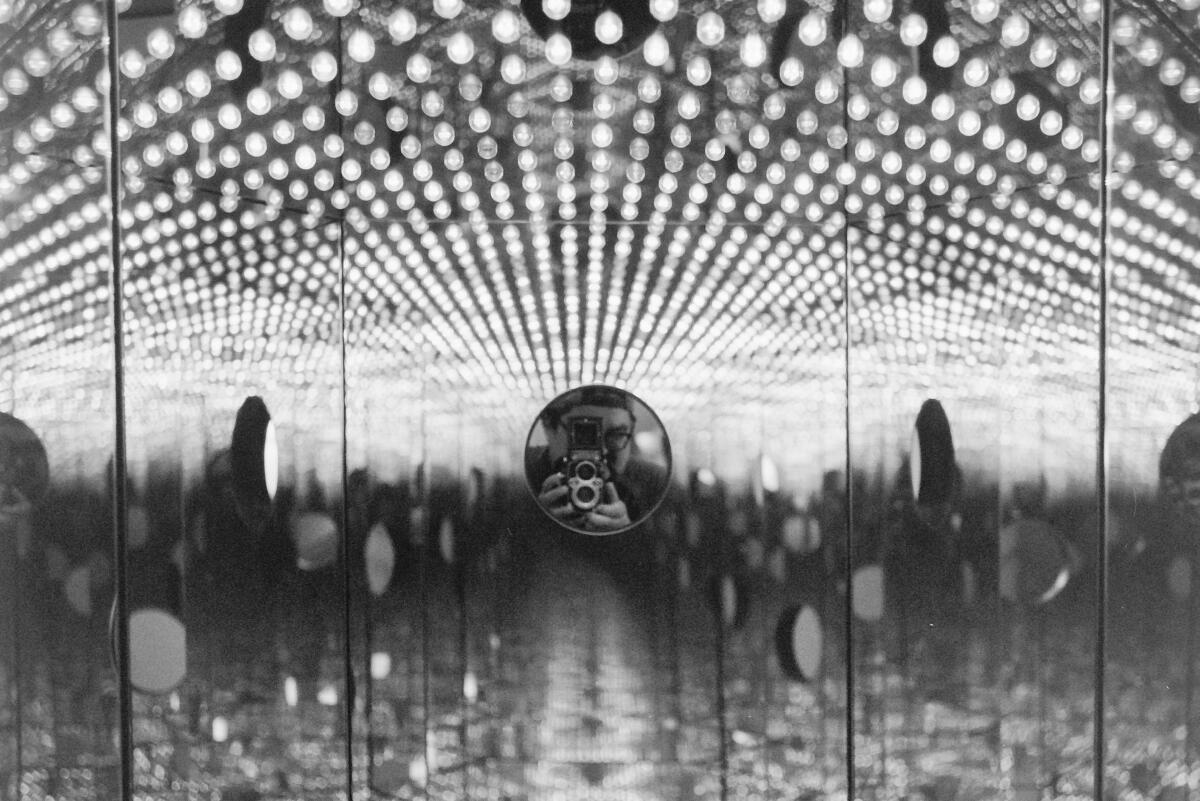

Yi gets lost in Yayoi Kusama's landscape of Broad on a day trip with old friends.

(Greg Yee / Los Angeles Times)

Today's great photo is from former Times correspondent Greg Yee, who died in January 2023 at the age of 33. Michael Chen and Natasha Avtandilians, two of Greg's college friends, reviewed hundreds of photos he took in Los Angeles and posted a selection of them on what would have been Greg's 35th birthday. “Simply put: his photographs are a postcard from home, from home,” they wrote.

Have a great day from the Essential California team

Jenny Gould, journalist

Karim Domar, Head of the Bulletin Department

Check out the hottest news, topics and latest articles on latimes.com.