Buyout firms are cutting interest costs by tens of millions of dollars by refinancing debt accumulated in private credit markets with publicly traded bonds and loans, providing a windfall to the Wall Street banks that regulate them.

Nearly $10 billion of so-called private credit loans have been refinanced in the public markets, with borrowers paying off stressed loans in favor of a cheaper alternative, according to data from Bank of America.

Private equity firms buying companies are benefiting from a recovery in global corporate bond and loan markets, after the Federal Reserve signaled that inflation has been tamed enough to start cutting interest rates.

The shift has opened the door for investment banks to aggressively squeeze business they lost to private lenders after interest rates rose sharply in 2022, as banks hope to revive lucrative fees.

“The pressure is coming from sponsors to lower coupons, and this is just a race to the bottom between banks and direct lenders,” said Neha Khoda, a strategist at Bank of America.

The list of borrowers switching from private debt markets to public debt markets includes Veritas-backed energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie and British insurance broker Ardonagh, according to people familiar with the matter. Ardonagh is owned by Madison Dearborn and HPS Investment Partners.

Other companies, including Blackstone and HG, have sought loans at discounted interest rates for new deals, as banks and direct lenders in the private credit industry often play against each other, as private equity firms look to trim interest costs.

It culminated last week in the sale of a $5 billion loan to support KKR's purchase of a stake in the healthcare technology company known as Cotiviti. Last year's aborted investment in Cotiviti was initially slated to be financed by direct lenders, as turmoil in public markets pushed banks to the sidelines.

But banks led by JPMorgan Chase have lobbied intensely to secure financing over the past four months as the new deal nears the finish line. The package they reached on Thursday included a $4.25 billion loan that pays an interest rate just 3.25 percentage points above the floating rate Sofr, a level well below the threshold considered by private lenders last year. The company also obtained a $725 million fixed-rate loan with a coupon of 7.63 percent.

The changing market conditions provide an opportunity for banks, which have been burdened with billions of dollars in losses on the deals they agreed to finance in 2022.

Severe inflation and rapidly rising interest rates have made it difficult for major lenders to shift loans off their balance sheets and into the hands of other investors.

This included loans associated with some large acquisitions including Elliott Management's acquisition of technology company Citrix, Elon Musk's purchase of social media company Twitter and Apollo's acquisition of telecoms group Brightspeed. The losses limited lenders' interest in making new loans, and when they did, the terms were often too expensive for private equity firms to pursue.

Private credit funds have stepped in to fill the gap, providing billions of dollars in loans to companies including Norwegian online classifieds company Adevinta and software maker New Relic, providing money at a time when cash was hard to come by.

“Direct lenders had significant market share gains from banks because banks were going through periods of stress,” said Kip Deaver, head of credit at Ares. “These market share gains are permanent, but they ebb and flow.”

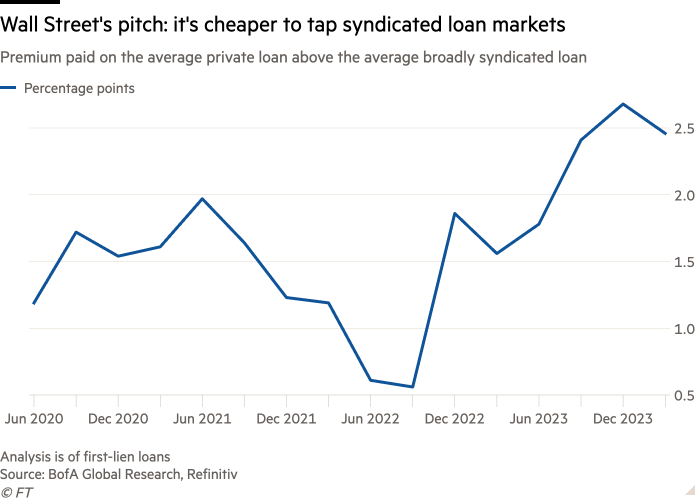

Khoda said the gap between the two worlds had not been this wide for at least a decade. By its calculations, direct lenders were charging approximately 2.5 percentage points more than banks. A year ago, that number was a full percentage point lower.

“As the year ends, you see banks becoming more aggressive,” said Chris Bonner, who heads financial capital markets at Goldman Sachs. “I've seen more stability in the ecosystem, [with investors] Feeling rates are finally dropping. . . As an underwriter, you feel more comfortable taking risk positions.”

This shift has increased pressure on private credit lenders, who are either rapidly reducing the costs they charge borrowers — in some cases waiving fees to keep deals in their hands — or losing those deals to traditional syndicated loan markets.

The issue may present less of a challenge for huge money managers that straddle both worlds, given that many of the giants in the private credit industry — including Ares, Blackstone and KKR — are also huge players in public debt markets. But investors say the direct lending funds they manage may start to deliver lower returns.

At a board meeting last month, an executive at the $105 billion Ohio Public Employees Retirement System said the generous return on private credit could shrink as competition intensifies. “I wouldn't be surprised in the coming years if we see some pressure in terms of the spread we can gain,” she said.

The pressure on yields has also been exacerbated by the scarcity of large mergers and acquisitions since the Fed began raising interest rates.

“There have been fewer LBOs and therefore less new loan volume,” said Michael Patterson, managing partner at asset manager HPS Investment Partners.

“Managers have not invested as much capital as they expected and…they want to make sure they participate in the next opportunity. They are willing to be aggressive to make sure they do.”

Underwriting fees for these risky deals in the United States have risen 35 percent year-to-date to $1.8 billion, according to data from the London Stock Exchange, and are up 10 percent globally.

However, the banks have plenty of room to recover, given that they earned about $11 billion from their leveraged finance business in the US in both 2023 and 2022. That was a third lower than 2021 levels, when they rose above $16 billion.

Risks still lurk, and bankers say they haven't forgotten how quickly things can fall apart like they did in 2022. But they hope now is a good time to strike, especially in an election year when markets may be more volatile.

Private credit lenders add that they are not going anywhere. Even as fundraising slows from its torrid pace, senior managers are still withdrawing billions of dollars each quarter to make new loans.

“In order to have an effective capital markets ecosystem, you want to get the banks involved,” said Melwood Hobbs Jr., managing director at Oaktree, an investment manager. “Everyone loses sight of the fact that this market is too big for just private credit or banks.”

Additional reporting by Sun Yu